By Kate Magee

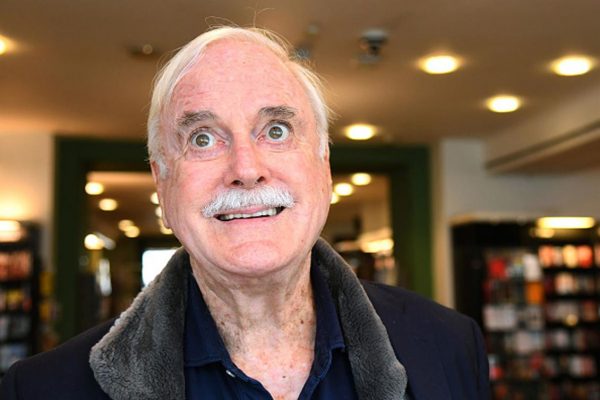

“I used to think creativity was all about furrowing your brow, trying awfully hard and cudgelling your brains. Now I take a 10-minute break,” John Cleese says.

“The more you take breaks, the more your creativity flows because you don’t waste energy on all the negative thoughts about yourself,” he adds.

Cleese is explaining to Campaign how his approach to creative ideation has changed over the 55 years he has spent in the public eye, most famously writing and starring in Monty Python, Fawlty Towers and A Fish Called Wanda.

In his latest book, Creativity: a Short and Cheerful Guide he explores the conditions required to have great ideas. It is a refreshing reminder for adland, an industry at real risk of burning out and losing its best talent, because it reinforces the importance of play and relaxation.

As the industry reckons with the shape of post-pandemic work, it’s a message that should be right at the heart of the debate: people need protected time and space to be truly creative.

Don’t grow up, it’s a creative trap

In his book, which can be read in an hour, Cleese mentions three key points about creativity, all sourced from academic research: the importance of play, that this “play” has to be separate from ordinary life and the power of the subconscious.

“The biggest killer of creativity is interruptions,” he says. He advocates establishing physical boundaries of space (find a private room) and time (at least a dedicated hour to 90 minutes) in which you are not available to others.

The ability to disengage from reality and play like a child is crucial to creative success. “Play has to be separate from ordinary life and everyday responsibilities,” he says. He likens it to a football match: the referee blows the whistle and the rules of the game apply. Spectators aren’t allowed on the pitch, and when it’s over, you return to normal life.

This is something that is increasingly difficult for adland’s creatives to achieve, with the rapid ascent of the cult of productivity and technological developments leading to an “always-on” culture. That’s before you throw in 16 months of a global pandemic, home-schooling and a lack of physical separation between work and home life. But as Cleese points out, we need to slow down if we want to produce quality work.

Once external stimuli are removed, the internal battle begins. “It’s exactly like the Buddhists say, your mind is like a glass of cloudy water, but if you just sit there, eventually the cloudiness sinks and you begin to get some clarity,” he says. A quiet mind is crucial to hear the prompts from the subconscious, which doesn’t use verbal language but offers up hunches or feelings.

Psychological safety is also key. There are no mistakes, just exploration. “The moment you start worrying about time pressure, or thinking you’re not good enough, that’s when you tighten up and your mind goes back to stereotypical thoughts because they are heuristics. But that’s not very creative. You want what happens when you’re not having stereotypical thoughts,” he says.

‘Without diversity, they come up with nothing’

Although his book talks about individual creativity, his career, like that of adland’s creatives, has been mostly collaborative. He wrote Monty Python sketches with Graham Chapman, and TV sitcom Fawlty Towers with Connie Booth.

His advice for working with others is simple: “If you want to have a creative group, you have to have diversity. If they are all, as they used to be, middle-class, middle-aged and white, they will report afterwards it’s been a very good experience, we thoroughly enjoyed it, we’d love to do it again, but they come up with fuck all.

“If you have a diverse group with a whole lot of people putting in different sorts of opinions, then that’s the way you get creativity.”

He warns, however, that diversity can bring social disagreement, which immediately interrupts creativity: “You want conflict of ideas, not individuals.” The person leading the group has got to understand the creative process and skillfully balance personalities.

“They also have to understand that creatives are not as keen on money as anyone else, but they are very keen on recognition,” he adds.

Why is creativity so undervalued?

And yet recognition of the importance of creativity is something with which our society struggles. Cleese believes it is a “tragedy” that creativity, a subject of “such enormous importance” is not being more widely spoken about. In particular, he is worried about an apparent lack of interest in the subject by the British education system.

Cleese was 22 before he discovered he had any creative flair, despite having the benefit of a “good” education – he is a privately educated Cambridge graduate. Indeed, he believes schools tend to accidentally erode creativity in favour of conformity.

“People are very, very easily made uncomfortable if they aren’t holding the same opinion as everyone else. But the essence of creativity is not to hold the same opinion. You need to respect other people’s opinion, but you need to try one on your own,” he says.

Cleese subscribes to the view outlined by Iain McGilchrist in his book The Master and His Emissary, that since the Enlightenment, our society has promoted rational, empirical “left-brain” thought as intellectually superior to the more intuitive and imaginative qualities of the “right brain”. This has led to the devaluation of creativity.

“Somehow people believe passing judgments and being analytical is more important than being able to do the work in the first place.” he says.“We have to fight against that.”

For example, he questions why the opinion of critics – who usually can’t do what their subjects can – are taken so seriously.

“I think very simply that it would be very self destructive of me to read this rubbish; not interested. If I want to get an opinion on a script, I send it to a director or writer. I don’t send it to a critic,” he says.

“The thing about being creative is you’re not sure if something is going to be any good or not. But if you want the same amount of praise as last time, then do the same fucking thing. You’ll never do anything special but then you’ll also never do anything terrible.”

Creative people are also more able to access their emotions and live with ambiguity, and this is something that should be praised. He encourages people to delay decisions, for example, because it gives you time to find new information or have a new idea.

“People who rush a decision to try to look decisive are actually cowards,” he says. “Creative people can tolerate the slight discomforts that we all get when something is up in the air and hasn’t been decided yet. Decisiveness is not making decisions quickly, but making decisions when they have to be made,” he says.

‘They think they know’ – how leaders strangle creativity

The deference to the left brain is also evident in the way organisations are structured. As Ogilvy’s vice-chair Rory Sutherland pointed out at Nudgestock, at which Cleese also spoke, there is an in-built asymmetry – creatives always have to ask non-creatives to approve their ideas, but never the other way around.

“It’s insane,” Cleese says. To illustrate the point, a few years ago, a (non-creative) executive at Disney asked him to make changes to a script. He listened politely to the suggested changes before replying: “I can’t do that because I don’t know how to make the script worse.” Needless to say, it never got made.

“I spend my life in front of audiences, writing stuff, making them laugh. You’ve never written a fucking script in your life. Why do you think you understand it better than I do?” Cleese says.

“When you’re flying, do you send suggestions up to the pilot? I think we should be dropping 300 feet? Why do they think they know? It’s incomprehensible.”

It’s a frustration with which many of adland’s creatives will sympathise. As Cleese says: “The people who tend to rise to the top of organisations, don’t tend to be very creative, they tend to be power brokers.” They instinctively distrust the creative process because it doesn’t seem very efficient, he argues.

Cleese has a simple piece of advice for those who are stuck with a boss who doesn’t understand the creative process: “You arrange an accident,” he smiles mischievously. “What else are you going to do? If the person in charge doesn’t know what they are doing, you’re in trouble.”

Indeed, when those in charge ask him what he’s going to do with a brief before he’s had time to work on it, he replies: “I don’t know what I’m going to do. Either you trust me to come up with something good or you don’t. And if you don’t, why are you employing me anyway?”

The creative ego and self-doubt

And yet like most creatives, he also has a healthy dose of self-doubt. In his book, he says he still feels fearful when faced with a difficult problem. “We’re all much more insecure than we’re prepared to admit,” he adds.

“[Graham] Chapman and I used to worry a lot in the beginning of Python when we’d have a day when we wouldn’t write much. We’d think ‘Oh shit, it didn’t work today’,” he says. But after a time, the pair realised that while the output of each day varied, they could write an average of 17 minutes of good material a week.

He began to recognise that the slow days were just part of the writing process. He gives this analogy: “When you eat, you don’t think the good bit is when the fork is bringing the food to your mouth and everything else is a waste of time.” There’s still music in silence.

Creative career longevity

At 81, Cleese continues to write and perform. He has recently written “a light comedy about cannibalism” called Yummy, which he believes is his funniest script yet. He is about to attach a Hollywood director to the project. He is also writing a stage adaptation of Life of Brian which he says is “very, very naughty”. “I’m hoping that on the first night the evangelists in America will burn down the theatre so it will run for years,” he smiles.

Career longevity seems to be problematic for many creatives in adland, where the average age is 34, according to the IPA. When asked why this may be, Cleese says: “The great thing about young people is that they are cheap. That is attractive to people running businesses who don’t understand creativity.”

He adds that people are always telling him about exciting new directors with whom he should work. But he says: “I don’t particularly want to work with an exciting new director. I’d like to work with a slightly boring, older director who knows what they are doing.”

When Cleese was making the film A Fish Called Wanda, the director, was 77-year-old Charlie Crichton. “He knew what he was doing. We used to finish at 6pm every day because he knew what he wanted to shoot. He would shoot that and then we were finished. Most directors make the film in the cutting room because they don’t have the experience to know how to make it on the floor,” Cleese says.

A block of paper and a pencil

Cleese, who now spends much of his time on the Caribbean island of Nevis, has taken his own advice about establishing the time and space to be creative. While he acknowledges that for many people the pandemic has been a really difficult time, he says, “for an old introvert like me, give me a block of paper, a few books and a pencil and that’s all I need to keep myself amused”.

As the world shifts into whatever post-pandemic life may present, it is worth remembering Cleese’s message to prioritise play, take breaks and retain a sense of perspective.

“What matters is doing important things. I often think that intelligence can be defined as knowing the difference between what matters and what doesn’t,” he says.

The secret he has discovered in life, is that not much really matters at all.

Picture credit: Main image and book image, Dave J. Hogan, Getty Images