In the first in a series of essays on Arab identity and culture, Omar Khalifa looks at the quality of creation, the sincerity of expression, and the authenticity of musical icons such as Umm Kulthum, Fairuz and Abdel Halim Hafez

No question about culture and identity is ever going to be sufficiently answered in words alone. The complexities of identity – any identity – are in a million little details that beg a question not about what that identity is, but how it is shared, learned and passed down. How it is defined and redefined, examined and corrected, and how – if such be the case – it retains some parts of it intact as foundation.

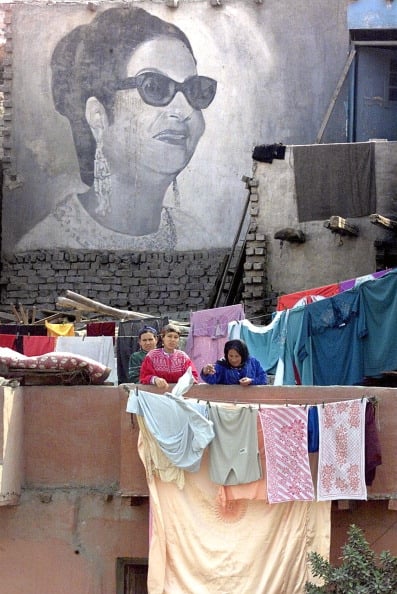

Trying to answer this question is as an arduous a task as trying to fit a beam of light into a wall-mounted cabinet. But then you zoom in a little closer and the vagueness of that answer will begin to recede, giving way to the slowly forming outlines of human bodies – certain human bodies that initially will look vaguely familiar, then familiar, then recognisable beyond all doubt; recognisable to the 400 million people of the Arab world. Ask them who they are, and they’ll tell you the names of the authors of that identity like they’re telling you the time of the day.

Arabs could trace the origins of the homogeneity of their cultural identity back hundreds of years, but the true advent of a popular Arab culture was in the middle decades of the 20th century, when independence movements spread like wildfire. Across the Arab world, Arab nationalist leaders came to power, including Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt, Ben Bella and then Boumediene in Algeria, Shukri al-Quwatli in Syria, and others. This political layer at the top found a solid foundation for actual political unity in the homogeneity of culture and language; a foundation fashioned with the voices of Umm Kulthum and Farid al-Atrash, the writings of Mahmoud Darwish and Tawfiq al-Hakim, and the leagues of films and theatrical plays that sprang out of Cairo and Beirut in every direction.

Generations were born into this new reality which was populated by its own unique cultural icons that were neither imposed, nor borrowed, nor synthesised. Radio and television signals sailed across the Arab world, shuffling dialects and familiarity, and solidifying previously disparate emotions into uniform expression.

The permeative nature of the impact these men and women had on Arab culture is most apparent in the way their artistic contributions have survived decades characterised by political turmoil, religious radicalisation, polarised successions to power, changes in general taste, and openness to other cultures, in addition to many socioeconomic factors that under normal circumstances are liable to bury any heritage deep enough to render any familiarity with it into an act of discovery.

The music of Umm Kulthum, which was created in what is now an unrecognisable era, is still intently and attentively listened to today: as buildings got taller and the streets denser; as exchange rates fell; as local cans of soda with Arabic labelling were replaced with imported cans bearing umlauts and diacritics; and as people changed their hairstyles and tuned the alertness of their hearts to the beep of a text message rather than the footsteps of a postman across the street, they still found Umm Kulthum’s Enta Omri accurately and quantitatively sufficient to tell someone ‘you are my life’. They still decoded every morning with Fairuz’s voice, even if she was singing about a war no longer fought and men no longer alive: the pitch of her familiar voice going higher and lower, forming Lebanese words; the first Lebanese to strike many ears, and no one pauses or squints; no on asks: who’s that singing? They know exactly who it is.

As times change and the ether is congested with an over-supply of artistic contributions, the work of those Arab icons has maintained an elite status propelled by the perceived quality of creation, the sincerity of expression, and the authenticity of what those icons represented and continue to represent, decades after their departure. They were the beacons of light and entertainment in a different era that didn’t accommodate widespread fame through technology or advanced means of communication, but the general public still sat down every Thursday, tuning their radios and opening the covers of books into many memorable evenings, confident that at the other end of this an artist has delivered.

To mention Abdel Halim Hafez’s name is to convey an atmospheric brand alive with intricacies and characteristics; to inspire confidence in the delivery of exactly that which is expected; the result of devoting immense skill, patience and creativity toward maintaining the high standards of integrity those icons set for themselves and would not go below for anything, or anyone. The outcome of this process is known to us now; it is that fundamental matter which continues to glow, forever preserved and handed over from a medium to the next, and will never dissolve.