By Assem Memon, cofounder & managing director of AdMazad

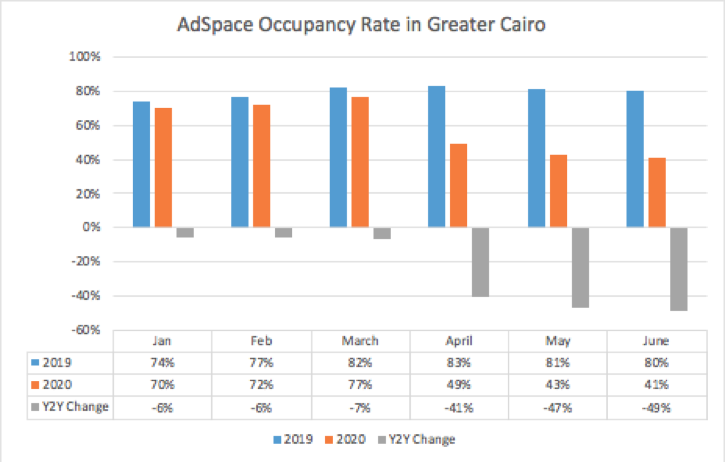

The out-of-home (OOH) advertising industry has been struck hard by the spread of COVID-19 – known as the coronavirus; however, the medium seems to have been facing a challenge before that. AdMazad, the data-driven ad-space provider for out-of-home (OOH) advertising, realized the noted shrinkage of ad-space occupancy even before the coronavirus crisis. Through COVID-19, however, there was a 100% increase in empty large billboards across Greater Cairo in the first week of April 2020, reflective of the spending sentiment of multinationals and large national companies during the COVID-19-induced #StayAtHome regulations.

From New York’s Times Square, to Cairo’s 6th of October Bridge, billboards accompany commuters worldwide on their ways to and from work. But what seems like a crowding of colorful sheets of plastic to the commuter – and potential consumer – is a multi-layered, complicated process for advertisers and agencies alike.

Aesthetics, content control, permits, licences, fees, taxation and zoning are all turning gears in the out-of-home (OOH) advertising sector – and if they are not, they should be. So, how can a very traditional industry become a 21st-century, modernized sector in Egypt?

The Industry

The annual turnover of the OOH industry in Egypt is estimated at EGP 6bn ($376m), of which expenditure is over 70% in Greater Cairo. As an extremely fragmented and layered market, there are hundreds of private and public ad-space owners and agencies.

In the last five years, the main driver of OOH usage was Real Estate advertising, representing over 40% of the entire market utilization in 2019. During the last 18 months, there was a surge in advertising from local and international tech companies, be it large organizations like Google or local success stories like Wuzzuf or Vezeeta. Future drivers of the industry will be more and more tech companies, particularly in food tech and e-commerce platforms, as well as FMCG products and commodities.

The Problem

Currently, the Egyptian market suffers from an oversupply of OOH inventory, leading to an occupancy rate of maximum 80% in high seasons. The visual congestion caused by the oversupply of OOH inventory leads to consumer irritation and a general frustration with the medium.

Moreover, given the layers of the market, the overflow of formal and informal brokers and sub-letters causes a visible lack of transparency amongst stakeholders and the government.

Hence, the fragmentation, lack of transparency, and the excessive visual congestion on Egypt’s roads need to be addressed.

The Solutions

Given the COVID-19 situation, a more flexible licensing mechanism that is focused on revenue-sharing rather than guaranteed revenues, will help concession and media owners reduce their overheads until the market recovers; furthermore, resulting in the asset owner being able to provide significant incentives to advertisers in down times.

In the medium-term, the government can increase revenue from OOH by reducing the number of licences and the overall supply. This would increase competition between media owners, through putting caps on both – the number of assets in inventory, and total square meters of ad-space available. Ultimately, this would result in maintaining – if not increasing – the revenue generated for government entities.

Beyond that, there are structural issues with the Egyptian market that have lingered for years. The industry needs to build trust and enhance its reputation. On the transparency and trust front, the use of a national database of OOH ad-space, supplemented with quantitative and qualitative assessments of the state of each ad-space would be a game-changer, especially if it was sponsored and funded by OOH owners. This database will allow advertisers to get a better understanding of the proposed plans and validate their investment choices, resulting in better service, lower booking costs and higher return on investment.

To address the consumer frustration of the medium, Cairo’s advertorial skyline needs to be freshened up through addressing the excessive supply of ad-space as well as revoking and dismantling outdated locations, establishing placement guidelines and standardizing inventory to reduce visual clutter. Coupled with an incentive program to terminate old and unused inventory, these changes would result in a more visually appealing skyline on the roads that is impactful to consumers and value-drivers to advertisers.

Tangibly, what does that mean? For one, concessions should not be given by a single “location”, but rather by “zone”; i.e 6th of October Bridge would be considered five large zones rather than 285 individual concessions. That should be accompanied by an increased minimum distance between ad-spaces, regardless of viewing direction. This change on its own should result in a reduction of ad-spaces by almost 20%.

Finally, there needs to be a coordinating body between the OOH regulatory authorities, namely local municipalities, governorates, road authorities and national roads corporations.

In conclusion, the Egyptian OOH marketplace has been pulled back by numerous challenges, part of which were driven by a gold rush mentality that resulted in a massive increase in supply, chaos in design, a reduction in transparency and the rise of the hustle. The changes proposed here would put a break on these drivers, resulting in increased transparency, reduced visual clutter, more engaging advertising opportunities, and overall innovation without really hurting the government’s purse.

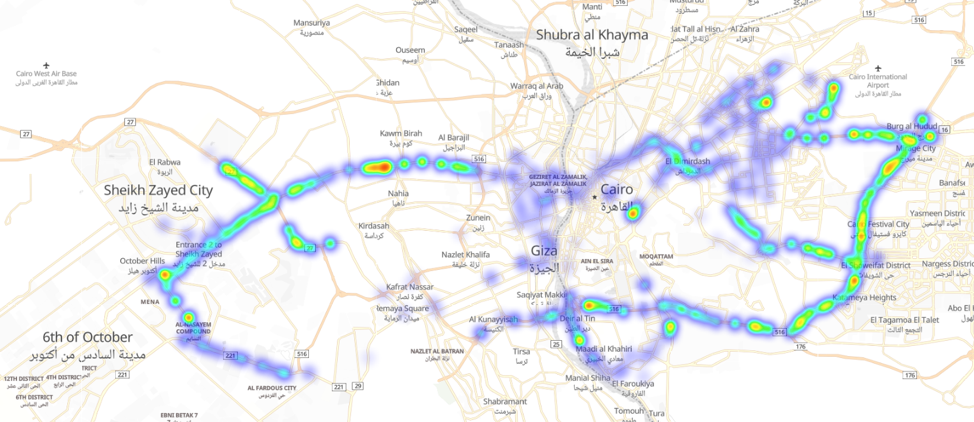

Average Speed when Viewing a Billboard in Cairo

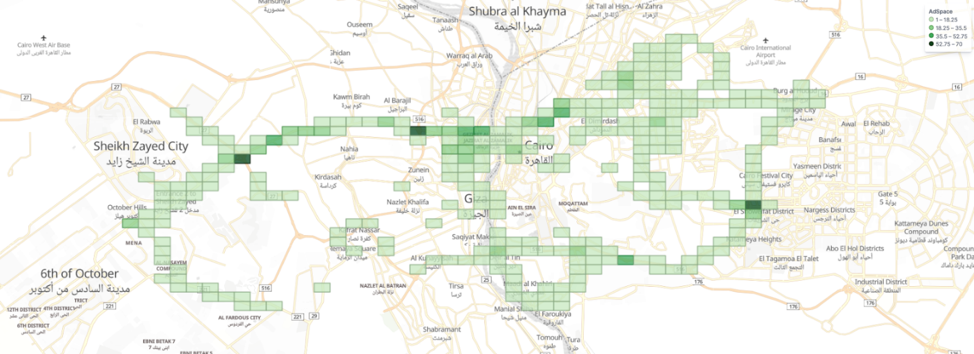

Ad-Space Density – Cairo – June 2020